Story //

Kristin Kirsch Feldkamp

Photos //

Atom Stevens

There was only one homeowner between Crowther and Daley, and that homeowner added windows in several locations throughout the home. “Those clerestory windows were not there,” says Daley, pointing to a location above a massive painting by artist Jerry Kunkel. “The previous owners wanted more light. In the bedroom they put in a window because Richard Crowther created dark spaces and very bright, light spaces.” The addition of the windows disqualifies the home.

Crowther came to Denver in the 1940s from San Diego to revamp Lakeside Amusement Park—you can still see his design work there in ticket booths. Rather than returning to San Diego and his former career in neon light design (or his home state of New Jersey), Crowther made Denver his home. In the ensuing decades, he designed countless other buildings (the Cooper Cinerama, the Esquire, Dupler’s Furs). He passed away in 2006. A trailblazer in green building, Crowther garnered international praise for his work in passive solar construction.

The Kunkel painting in Daley’s home is a great abstract piece that can be deceptive. “There are more colors than meets the eye,” says Daley. You have to take the time to look for them. Kunkel’s work is well known in Colorado. He was an art department faculty member at CU Boulder for over thirty years and passed away in March of this year.

Like Kunkel’s painting, Crowther’s designs can be deceptive. He was ahead of his time and his homes, especially the ones he built for himself, were opportunities for him to try out green theories. But to appreciate how advanced Crowther was, how innovative, you have to take the time to really look at his designs.

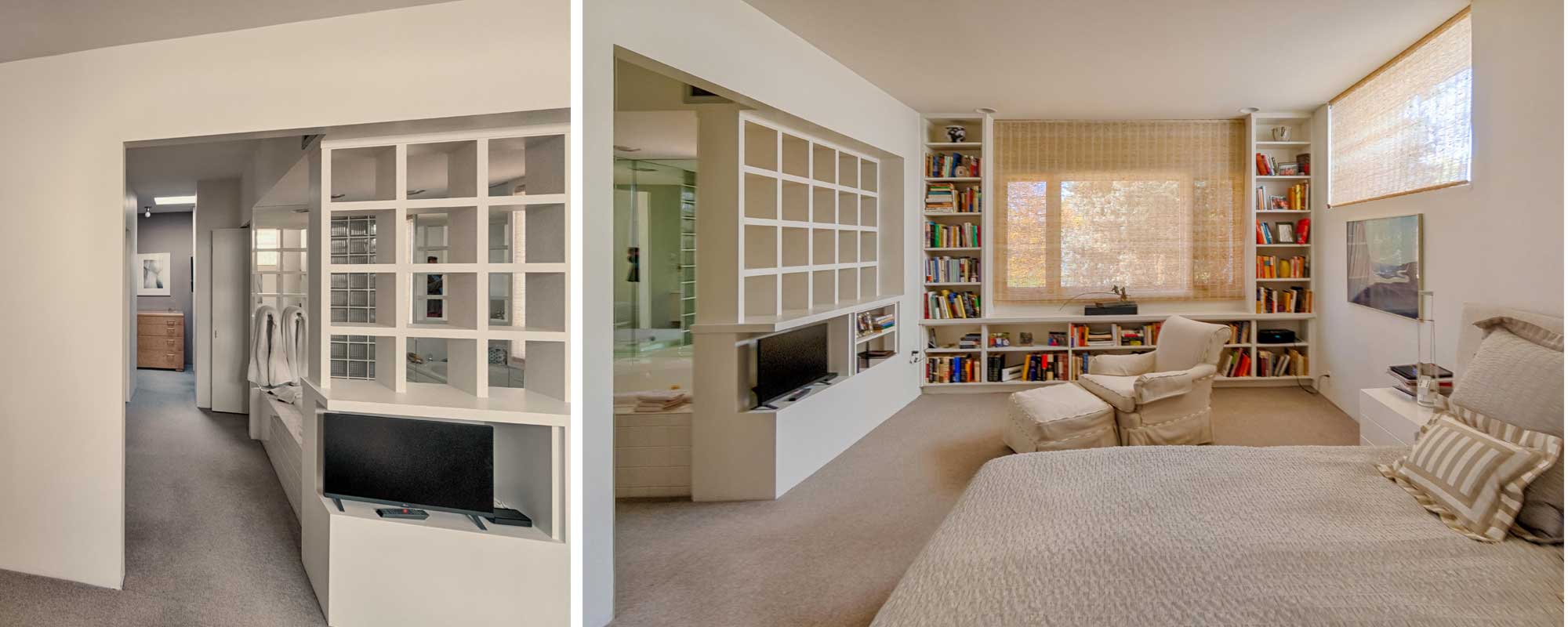

Crowther built Daley’s home in 1972 and throughout one finds evidence of his experiments with passive solar construction. Skylights—especially a large, round dome over the dining room—allow Denver’s bountiful sunshine into the home in specific, concentrated locations. Even the garage has a skylight. The home has an unstuffy, user-focused, modern sensibility. “It’s amazing how a well-designed property, well-designed space keeps on being very appropriate. As time moves on, there are ways to adapt it and use it,” Daley says.

After living in Daley’s home, Crowther built an even more progressive home a few blocks away where he lived for the remainder of his life. Daley had Crowther over to her home once and she says he approved of the edits she and her family made, like a kitchen update, that were cosmetic and not structural. In hindsight, she wishes she had asked him more about the home. Her home is one of a dwindling number of Crowther-designed residences left in Denver. His own home down the street is slated for demolition, something Crowther fans and historic preservation devotees are upset about.

Architect and urban designer Alan Golin Gass, FAIA, knew Crowther and joined two other Denverites, Mike Hughes and Tom Hart, last fall in an appeal to Denver’s landmark commission to prevent demolition of the Crowther home. Hughes, president of the Hilltop Neighborhood Association, lives in a restored Crowther home. Hart, an architect, is a board member of Historic Denver and DOCOMOMO Colorado. The appeal failed, but the conviction that Crowther homes are historically important to Denver hasn’t wavered.

“Denver has a sad history when it comes to the preservation of potential landmarks of mid-20th century architecture and the periods immediately preceding,” says Gass. He lists a few historic buildings that have been demolished. “Boettcher School for Disabled Children by architect Burnham Hoyt; The Central Bank Building by architect Jacques Benedict; Currigan Hall by architects Muchow, Ream, and Larsen; May D&F Skating Rink and Hyperbolic Paraboloid by architect I. M. Pei; the original Skyline Park by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin.” He could list many more.

Daley thinks the problem lies in lack of historical appreciation. People notice her home because it’s different, but she doesn’t think there is much genuine appreciation and understanding of Crowther. “For a long time, we had a frame house next door and trees in between, and then they sold it for the lot and the house was scraped and a duplex was built—the Cherry Creek story,” she says. But there are holdouts, she says. The walkability of her neighborhood is one of her favorite things. “But as you walk around you think hmm, that’s endangered.” She’s hoping Denverites will stop and take a closer look.

Our interview with Ann Daley took place last fall at her residence. Daley passed away this April at age 88. You can read more about her life and legacy here.